Mishi Goes Myth Busting: Performance Air Intakes - Part 2

Look under the hood of any modified vehicle, and there's a high chance you'll find an aftermarket intake. But despite how prevalent aftermarket intakes are, there's still a ton of misinformation about them floating around the internet. In this post, we'll look at a few more intake myths and provide some more facts to combat the hearsay on the internet. If you haven't already read through our first intake myth-busting post, be sure to check that out here.

Myth #5: Aftermarket Intakes Don't Make Power

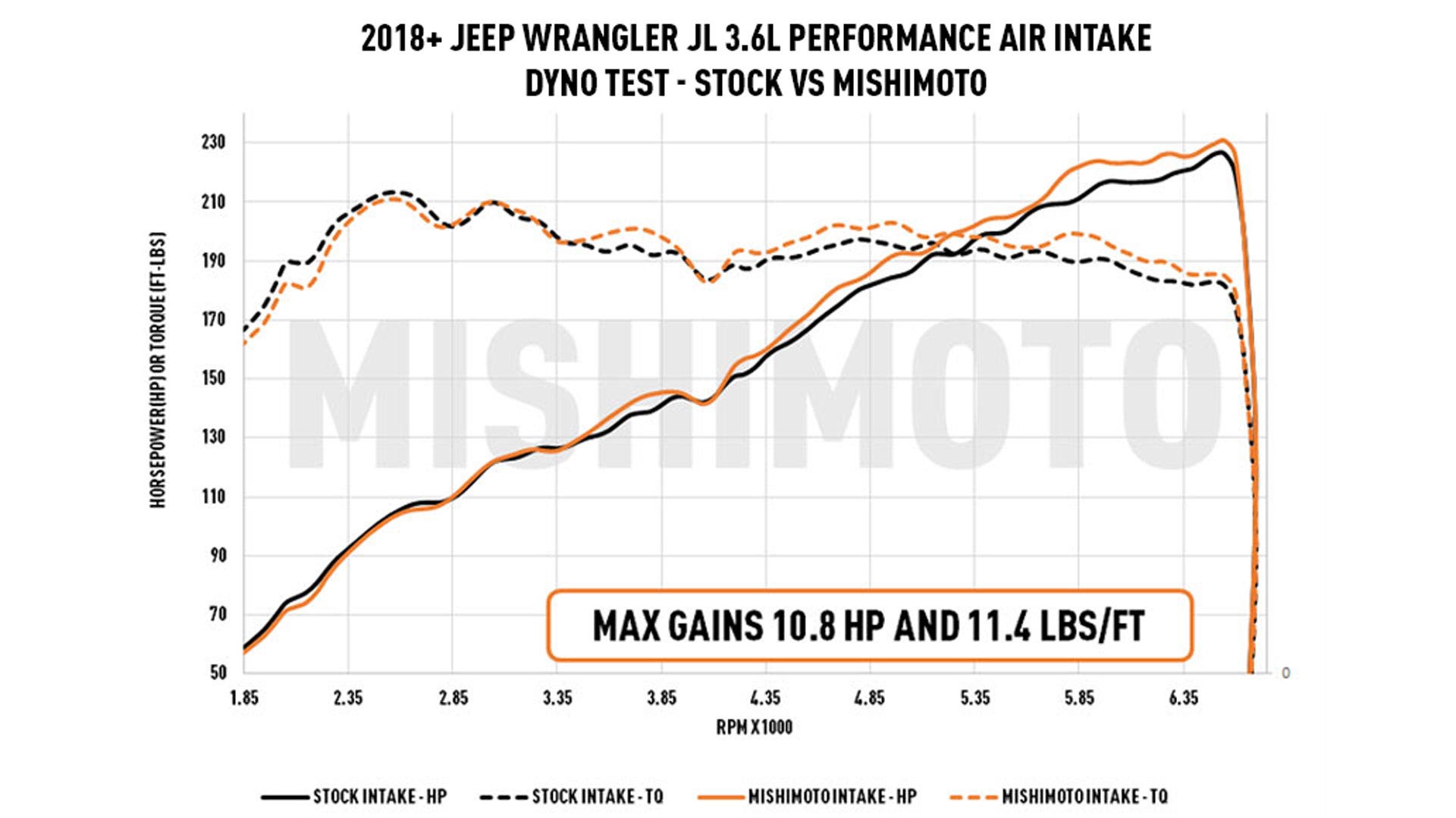

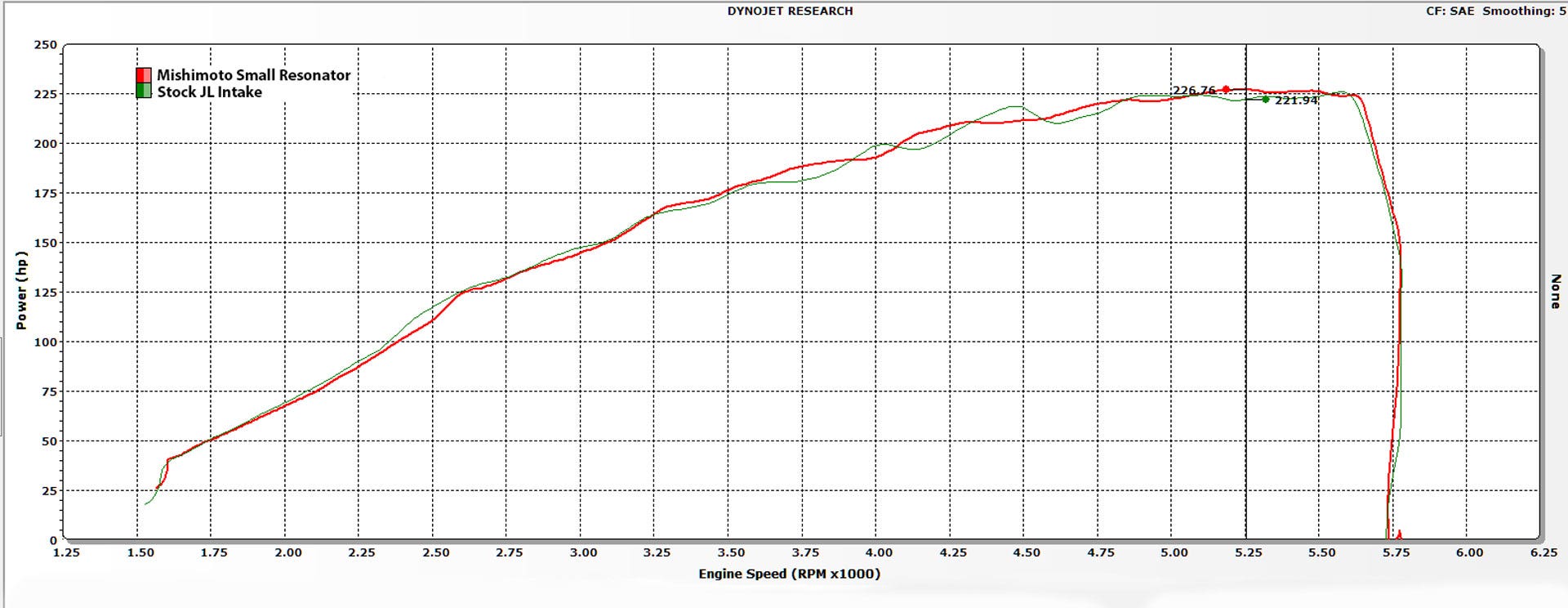

For some vehicles or intakes, this is true, but many engines and intakes can produce noticeable power gains. An engine is an air pump, and how much power it makes is directly related to how much air it can pull in and exhaust. If the factory intake is very restrictive, you could stand to make a lot of power by improving it. However, most modern factory intakes are not so restrictive that they're leaving 20 to 30 HP on the table; it's usually more like 5-10 HP at most.

The engineers at any OEM are given a budget, a power figure to hit based on competition or market needs, an envelope to fit all of the components into (the engine bay), and various laws and regulations to fall within. The engineers then have to make the best flowing intake they can within those parameters. For the most part, this yields an intake that 99% of the manufacturers market will never have to think about. But for the remaining 1% who are enthusiasts, there's often something to be gained from a better flowing intake.

On modern turbocharged vehicles, an intake likely won't make power without an ECU tune. Turbocharged engines operate within a much smaller margin of error, so the ECU is programmed to hit a target torque within a target air/fuel ratio and not deviate from those specs unless there's an issue. No matter how much better the intake flows, the engine won't pull in the air unless it's told to by the ECU.

On the other hand, N/A engines often have more straightforward engine control strategies and a wider tolerance for power. The above still applies to a point, but the ECU often allows a slight bump in torque output. As long as the fuel system can push in enough fuel to hit the target air/fuel ratio, and the engine can take in the extra volume (as well as exhausting it), the intake should increase power.

Myth #6: Aftermarket Intakes Shift the Power Band Out of the Useable RPM Range

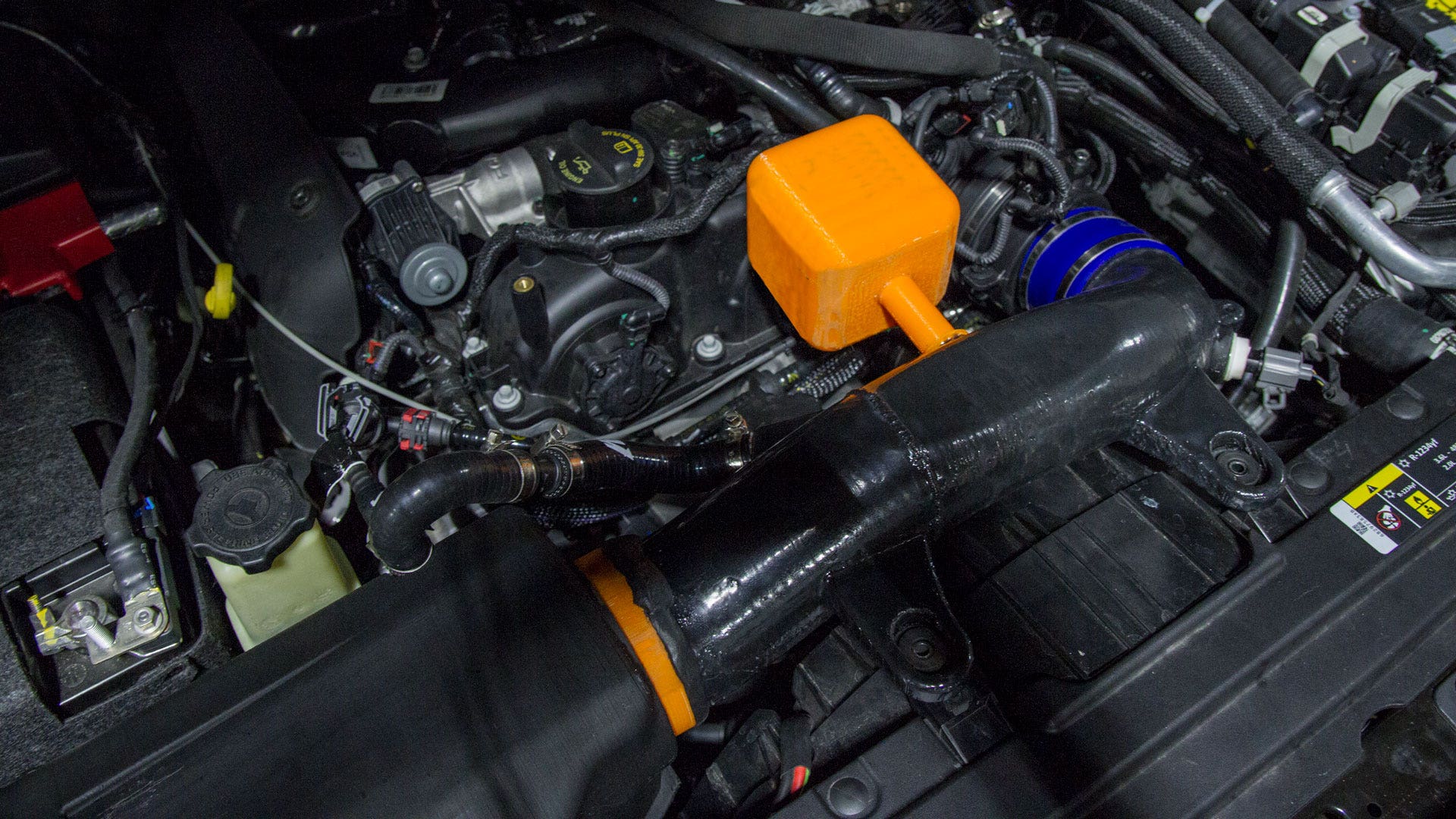

This can also be true if the intake isn't properly designed. It's common to see intakes that are just a filter on a large diameter pipe with nothing else. However, if you look at many stock intakes, like the one equipped on a 2018+ Jeep Wrangler JL, you'll see several chambers branching off of the main tube. Those chambers are resonators, and a lot of people believe their only purpose is to reduce induction noise. But, these chambers serve a performance purpose as well.

They're what's known as Helmholtz resonators, and to put it simply, they help improve the volumetric efficiency of the engine. Resonators do this by bouncing air back into the intake at precise times to coincide with the engine's intake valves opening. We go over this concept in-depth here. When tuned correctly, these resonators can change the RPM range in which the engine reaches peak VE and keep the power in the useable RPM range.

Myth #7: If a Vehicle Needed "X" Performance Part, the Manufacturer Would Have Included It

As mentioned above, vehicle manufacturers give their engineers a budget, an envelope, regulations, and many other restrictions to build within when designing parts. There's always a trade-off between performance and those other factors. While the parts they design work for 99% of the OEM's customers, those who want the most out of their vehicle can often find value in upgrades. It's also worth mentioning that there are many examples of the same engine making significantly more power in other vehicles that command higher price points or have more performance-seeking audiences. For example, the same 3.6L Pentastar found in the Jeep Wrangler makes 305 HP and 268 lb-ft of torque in the Dodge Challenger, 20 more HP, and 8 lb-ft of torque than in the Wrangler. Much of this has to do with ECU tuning. Still, we often find that the same engines in performance vehicles are equipped with better performing ancillary parts than their non-performance cousins - including the intakes and exhausts.

Hopefully, this has cleared up some of the confusing information you may have encountered in your search for information about performance intakes. If you have any more myths you want us to bust, or if you want to see us tackle any other parts, let us know in the comments below!

Thanks for reading,

-Steve